Mercy Gallery, Loomis Chaffee School - Windsor, CT

by Patricia Rosoff

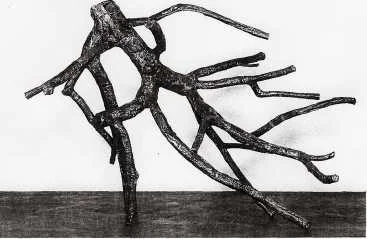

Bryan Nash Gill, Malus, 2005. Copper, lead, and apple tree, 57.5 x 77 x 68 in.

The central tension in Bryan Nash Gill's work is generated from its relation to landscape, so often the province of painting. Gill's is a sculptor's take, however, literally and metaphorically. His work is clearly composed of nature-tree branches and bark, woodsy flora like fungi and cabbages, leaves and seed pods, as well as deer hides and even desiccated orange peels. Still, what is striking about a gathering of these forms in a gallery, translated as they are by sub-tractive carving, reconstruction, and recasting, is the way they insist on an aesthetic of first-hand experience.

Gill's background as a lifelong woodsman and hunter-a naturalist as well as an artist-is implicit in these forms. They represent a response to the touch and smell of the natural world, expressive of how he finds it, and where. Rather than framing conceits producing a "window on the world," his sculptures are objects concerned with touch in relation to the human body.

Gill's strategy is to construct an experience for the viewer, with objects laid, sometimes literally, at our feet. Viewers must watch out for their ankles, thread a path between rising tree trunks, and duck around projecting branches. The formal relation is always dynamic: things rise, or crane, or list, or fall. They bloom up from the floor on slender stalks; they erupt in cantilever fashion from the vertical plane of a wall.

For Gill, the descriptive is always active and associative: his forms branch, fork, nest, encircle, and dangle. The works are intimately tactile, often phallic or vaginal, and their surfaces crackle, splinter, and shimmer-all within a natural spectrum of color or in patinated bronze, lead, and copper.

Gill's consideration of nature is compellingly active, expressed in the cycle of organic life: his forms do not merely stand, they sprout. He does not so much borrow natural form as activate it, conjuring the living from the dead. His sculptures are at once mythic and elemental. In Quarry, a deer hide is shaved into a topographical relief-an image of grasses and rutted dunes as sensuous to the hand as to the eye. In Blade, a slab of pine stands upright like a grave stele, the delicate tracery of its growth rings combing the vertical surface like the trailing drizzle of rainwater or the eddying whorls of a stream. In Malus, a tree branch is immortalized as if in a reliquary, its hand-like form plated in lead and copper, poured out like a root system or a river into volumetric space. Gill's prints and drawings are not so much two-dimensional images as they are fingerprints of forms-the smear of oily pigment or the embossure of inked wood grain on the surface of paper.

Gill pries nature apart, examines it through an inverted mirror, transcendentally but also existentially, and then recasts it. The chief qualities of this work are its relentless physicality and its insistent poetry.