Wheels in the Fields: Bryan Nash Gill

by Patricia Rosoff

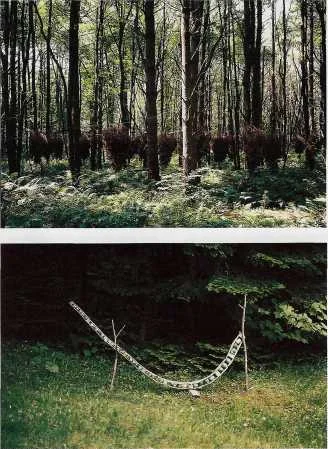

Top: Untitled, 1994. 1/4-mile of wire and 32 fir trees, 10 x 60 x 67 ft. diameter.

Bottom: Untitled #2, 1994. Poplar and cuprinol, 42 x 108 x 3.5 in.

"Wheels in the fields" was the phrase that popped up in one of Bryan Nash Gill's graduate school critiques at the California College of Arts and Crafts. It was an image of old farm implements rusting amid the rising growth of a farmer's field that this Connecticut farm boy had carried in some forgotten back pocket as he peregrinated from New England to New Orleans (to study glass blowing), to Italy (to study stone carving), to California (where he sought to discover the difference between art and craft), and to various primitive cold-water studio/ aeries in Colorado deserts, California mountainsides, lower Manhattan, and the northern extremities of Maine (where he later set up shop).

After 16 years, however, he came home to the very farm in the western Connecticut hills on which he grew up, which he has since bought and converted into a home and studio complex. For all the study and experience he gathered in his travels, in the end it was returning to New England, to its woods and its history both geological and anthropological that gave him his voice as a sculptor. It was from this place that he first made art that connected to the deeper roots of his sensibility. That first work composed of 42 Christmas trees suspended upside-down, in echelon, in situ, above the floor of the forest contained many of the elements that would come to characterize his mature work as a sculptor. For the first time, says Gill, "I wasn't making something for somebody to buy. I wasn't making something to please somebody else. And I [certainly] wasn't 'making it big, painting it red, throwing it in the field and calling it art.' The only people who saw [this work] were people I brought to it, or who stumbled upon it, like my family when they cross-country skied or walked in the woods. It was very uplifting, very eerie."

More importantly, it directly integrated the experience of a life lived out of doors (Gill is a lifelong woodsman, hunter, and naturalist) with the experience of making art, which is to say, in this case, with upending experience itself. This was art that took on not only the issue of how such a piece is encountered (via surprise and in a real-world context), but also how it is set out (in chorus, but aloft and uprooted) and how it accounts for the poetics of time (by the quiet shed of dead needles amid towering living specimens).

Twins, 2000. Saplings, installation view

In the most deliberate way, since his return to New England, the nature of Gill's work - its medium, metaphor, syntax, meaning - has been rooted in nature, particularly the grown-over tangle that is rural New England. But it is equally rooted in the evidence of time, of life cycles, of human labor and art.

Gill works in wood, gathered in winter forays and sledded back to his studio over snow-covered ground. He takes apart these logs, branches-even whole trees-and then puts them back together in the studio, employing any process that suits: splitting them, slicing them, carving back into them, stripping them of their bark, flattening the bark, even casting elements in bronze. Gill's is an artistic language doubly informed- by nature, certainly, but also by the conventions of the art world he set out as a student to find. What is so interesting about his work is the way in which it grounds its metaphor in the context of both.

Position is central to Gill's sculpture, something he describes as paying attention to the way things stand up. In Twins, a bronze cast in 2000, he conjoins two sapling trees butt-to-butt, laying the line of their married trunks laterally above the gallery floor. In so doing, the choreography of the branches presents itself-a double helix of stick-arms and stick-legs, cupping at each crown like the arms of a ballet dancer, straight-legged and tip-toe in the central passage, their skewering "horizon" dividing the mirror image like the reflective surface of a pond.

Beyond the form and the suggestive-ness of form, Gill's control of color orchestrates richly "organic" patinas against sudden glints of polished bronze, heightening the effect with evidence of its casting-revealed in the delicate web-like flashings that cling, surprisingly leaf-like, to many of the twigs and branches. "I like the objects to have flashing, and I tell my [foundryman] to make the mold weak," says Gill. "Then I edit the flashings or the air holes or what have you. It gives the object its own history; it's not like a brand-new polished thing. Even though out in nature there are brand-new polished things emerging all the time, I like the [record of] decay, because it has that sense of the whole cycle: it was green and young, and now it is dying."

Often Gill's work hinges on a dynamic tension between artistic processes and conventions and those of nature. A series of his early carved pieces manages to "free" melon-shaped balls within the sinuous branching of tree forms, creating "peas" in cage-like pods via sub-tractive sculptural process and providing a wry restatement of Michelangelo's metaphor for the art of carving.

Blow Down, 2001. Spruce bark, 43 ft. long.

In Blow Down, a recent work, Gill skins an entire spruce tree of its scratchy hide, which, after being flattened under weights for a year, is then tacked to a series of wooden stretchers and mounted (in a continuous 43-foot stretch) to the gallery wall. The striking thing about this work is its perspecti-val effect: the diminishing circumference of the tree (as it rises from root to crown) is equated with the triangulating perspective of foreshortening. By flattening the tree, the artist gives it back to us, as "drawing," re-creating how we would experience it in the woods, as it appears to taper out of view.

Back in the woods, near the studio Gill built for himself out of hemlock and pine timbered off the property, the location of the fallen tree is marked, in absentia, by a garland of grape vines. Here, in a hoop "drawn" on the forest floor, circling the up-pitched stump of its roots, Gill marks the spill of light created by the break in the overshadowing canopy of trees.